During the three weeks that I spent there, almost always alone, taking my measurements, the magic of this civilisation, the essence of which I was unaware of, stole into my heart. And then, during the ten years that I lived in Peru, and with the dozens of journeys that I made, during my nights under the stars, I dreamt about the day when I would be able to share these unique sensations with others.

How does the actual writing process occur?

Jean-Daniel Baltassat: One of us two puts pen to paper…

Antoine Audouard: …then, he sends what he has done to the other, who corrects it, makes suggestions, bringing his own particular flair, and then it is his turn to start the writing process… the text goes to and fro until we are happy with the result! And as time goes by, it becomes harder to determine which one of the two did the original writing… It becomes a process of fusion. And it is something of a miracle, because literature has the reputation of being the domain of unbridled egos!

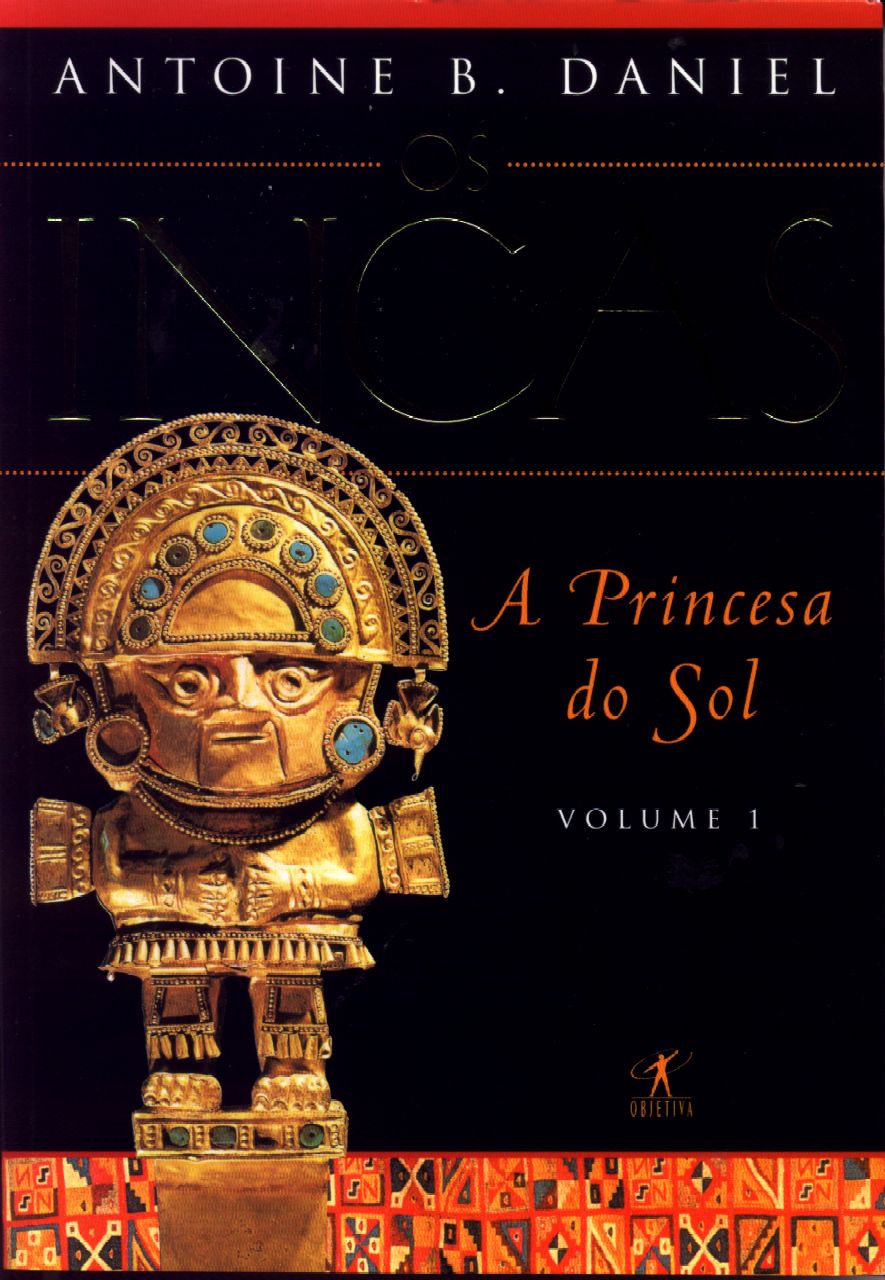

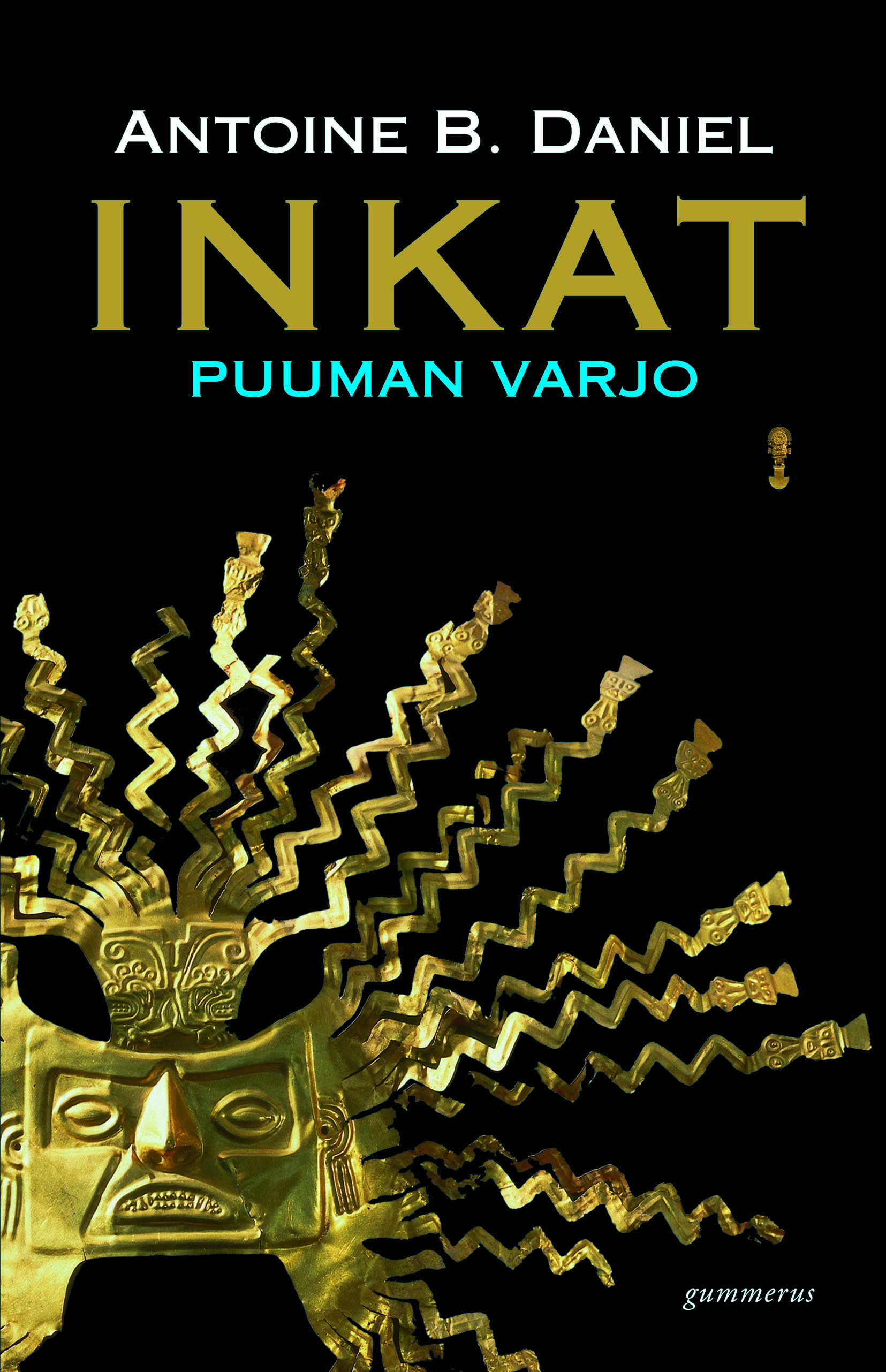

This didn’t occur between us for one simple reason: we were so very keen to bring this project to life that we immediately got rid of any such tension. The first great pleasure in this adventure was to feel the emergence of the identity of its author: “Antoine B. Daniel”, which is really none of us while encompassing aspects which are deeply personal to each one of us.

When did you spend time in Peru and how long did you stay?

Jean-Daniel Baltassat: It was a year ago. It was quite an amazing trip, during four weeks. Our starting point was the place where the Spaniards arrived, on the actual beach where they landed, 170 men and sixty odd horses setting out to conquer an empire… We saw the little red crabs that would have scuttled ahead of their steps, we discovered the balsa wood rafts upon which the Indians had sailed, followed the flight of the pelicans high above the mangrove setting – and in the distance we saw for the first time the foothills of the

Andes, the mountain range which filled the Spaniards with such admiration and fear.

Antoine Audouard: We then retraced their steps as far as possible.

We already had our stories in our heads, even right down to the details, but this face-to-face encounter with the reality of the locations and the local people’s faces really “shook us up”: everything was different, bigger, more powerful…

Bertrand Houette: …and yet, in certain areas, we literally “recognised” places that we had lived in our imagination. The encounter was very rich in emotion: not only the juxtaposition between the mental picture we had built and the images of real places and people, but also the sense of how reality is transformed by the force of imagination…

Jean-Daniel Baltassat: We went for a dip in the hot springs of the Incan king, at Cajamarca, exactly where he himself would have made his ablutions during the last three days before the great massacre of Cajamarca. It was night-time, we were in this boiling spring water, with steam floating around us, and we felt a kind of presence…

Antoine Audouard: It was a magical sensation that took hold of us. When we came to Machu Picchu, we saw in the dawn with its humid mist thick enough to hide away ghosts from view… And at the summit of the mountain, which somewhat resembles the wing of a bird, we perceived in a very powerful way the existence of the universe, the feeling of a break in the frontiers of time and space.

Jean-Daniel Baltassat: One of the characteristics of the Incan universe is the extremely powerful evidence that it left of its civilisation, terribly moving and at the same time relatively rare because there was an enormous amount of destruction. At each spot, Bertrand guided us, helped us to reconstruct, to “re-people” the place in a manner of speaking.

Bertrand Houette: We must remember that the Incas did not have the gift of writing; therefore all sources about them are Spanish, or if not, if it is an Indian source, it is the fruit of Spanish acculturation, after the conquest… Neither is there a graphic universe, or practically none to speak of, there are very few objects, etc. Contrary to other Andean civilisations that preceded them, there was no real Incan artistic blossoming. They were great builders and accomplished gold and silversmiths: according to the descriptions which witnesses have passed on to us, their work was apparently quite sublime! Few Spaniards were sensitive to the beauty of these treasures and the greatest part of it was melted down… This might seem a paradox to us now, when we think that this happened in the XVIth century, the great Spanish century, Charles the fifth, Velázquez, a great artistic and cultural period. But that would be to think in our own terms and not from their perspective.

Are there any monuments or palaces that remain?

Jean-Daniel Baltassat: Yes, some important and indeed splendid sites remain, endowed with highly evocative spiritual force, each with its own particular type of magic and which, in our own way, we “visit” in the book. But there only remains the structure of the monuments.

You also need to remember something particular about the Incan world: they were people who lived in a universe that was totally steeped in the spiritual, as much in their everyday life as in their way of perceiving, as we would say today, their own relation to the world.

Bertrand Houette: With the Incas, not one stone was placed which was not imbued with meaning – according to its position, its size, its function…

Antoine Audouard: The Spaniards instinctively measured the strength of the Incas’ sacrality. They both destroyed it and reconstructed it, demolishing a great number of temples while rebuilding churches on their foundations using the original walls. It’s a kind of Incan irony that, years later, with the earthquakes, the churches collapsed whereas the Incan masonry stood firm.

How can we explain this terrible conquest?

Antoine Audouard: When we look closely at these events, our reaction is one of shock: how, in twenty-four hours, did a group of 170 men with sixty-odd horses manage to beat an organised army of 80,000 men? It is still with wonder that we think back to the outcome, the mystery of which remains to a certain extent to this day, despite the many historical elements at our disposal.

Bertrand Houette: It was a founding event as well as a destructive one: a single battle experienced on the Incan side, as a trap, a massacre, a catastrophe, and from the Spanish side as a great victory of cunning and courage… At Cajamarca, we walked up to the hilltop reached by Pizarro and the Spaniards – followed by some Indian troops that were hostile to the Incas. One has to try and imagine the picture that presented itself to them: this immense plain stretching before them, nestling in the mountains, and along the slopes white tents as far as the eye could see. They can hear all these people singing, they hear the sound of drums, horns, because the Incan king is fasting, and there are going to be great festivities the next day… And in twenty-four hours, they have taken the King prisoner and massacred 6,000, 8,000, maybe even 10,000 people! Even for the Incas, a warrior people, conquerors, just out of a cruel civil war, it must have been a staggering scene. And they were never to regain their power.

Jean-Daniel Baltassat: This is certainly the moment that inspired the romantic setting of the story, the situation between our two protagonists: two young people who meet and whose fate becomes one, just as all around them everything is destroyed. On the one hand, a conquistador who will participate in the battle, who will play a prominent role… and on the other hand, a princess who holds a very special position next to the Incan king…

Bertrand Houette: We imagined them at once very representative of their respective worlds while at the same time “different”, marginal for one reason or another…

She is called Anamaya…

Jean-Daniel Baltassat: She is an Incan princess whose origins are considered mysterious and rather disquieting by her own people: she has blue eyes – which is unheard of for an Incan. Yet she finds she is the repository of secrets, imbued with an essential knowledge and understanding of the past and the future of the Empire.

Bertrand Houette: Within the interior of the Incan world, she becomes a magical person, recognised as such by the Incas themselves, and in fact she does indeed play a part in this very particular universe where everything is a sign, where everything reveals a presence of the Gods, where there is therefore a great submission to the visible outside world, because the invisible world is everywhere…

Antoine Audouard: … When a man’s hand touches a rock, it sculpts it a little to tame the Gods, to speak with them…

Jean-Daniel Baltassat: Anamaya moves from the visible world to the invisible, which the Incas call the “the other world” or the “netherworld”…

Antoine Audouard: … the moment when this catastrophe and massacre occur, Anamaya’s capacity to move between these two worlds give her an immense strength: she becomes a point of reference in this Empire which is losing everything it cherishes… From the moment when the Spaniards put their hands on Atahuallpa, it is practically as though the universe disappears! One does not touch the King, or else the sun will extinguish itself… But Anamaya is the symbol of something which can link them to their past, something which can link the “world up above”, which has just been subjected to unthinkable

destruction, with the “World down below”, a world of hope which offers the possibility of transformation… Something however goes wrong, she falls in love…

And the young man ?

Jean-Daniel Baltassat: The story of Gabriel appears on the surface of it less complicated, and in any event more familiar. He is a European scholar influenced by the atmosphere of intellectual freedom which reigns in certain Spanish universities, such as Salamanca. He comes from a rich family, but he is a natural child… When we meet him at the beginning of the book, he is in a jail of the Inquisition for a minor offence. His father gets him freed but, at the same time rejects him, “disowns” him… On the psychological front, he is a completely free man but equally absolutely alone.

Antoine Audouard: It is the same with many of the conquistadors…

Francisco Pizarro himself was born out of wedlock, like his crony, accomplice and in the end enemy, Diego de Almagro.

Jean-Daniel Baltassat: Gabriel is thus a man for whom the conquest of Peru is first and foremost a voyage of self-discovery. He is on a quest to find something, which is not gold, which goes beyond recognition and glory… And he finds Anamaya, and through her the world of the Incas…

Antoine Audouard: first of all he comes of age: he is very young, and has not really had to face the violence of men. But he discovers the pleasures of being brave, of being in a position to exert a certain influence, albeit in the shadows, through his intelligence and his discretion. For him as well, love is a definitive revelation, a mistake, but something which opens up his heart and utterly bowls him over. His encounter with Anamaya opens up his universe.

Bertrand Houette: But the context within which this meeting takes place renders it at each stage more difficult and painful. Each of the two rival camps never miss an opportunity to bring home to the two youngsters where their loyalty should lie: this continually places them, all through the book, in impossible situations.

Jean-Daniel Baltassat: well, nearly impossible!

How did you incorporate the characters of the novel with the historical figures?

Antoine Audouard: We now sometimes find it difficult to see the difference! Thanks to the interplay of ideas with Bertrand, our five fictional characters have become part of the historical record without disrespecting the truth of the past. And dozens of characters from the history books have become major players in the novel. Francisco Pizarro, for example, fascinated us: the more we delved into his complex personality, the more he seemed to us totally odious and absolutely amazing at the same time, possessing an astonishing courage – but they were all brave, that we can grant them! -, as well as great intelligence, sensitivity, an

unquestionable spiritual dimension, while still being able to commit the most basic atrocities, without batting an eyelid…

Jean-Daniel Baltassat: …to end with a tragic destiny.

Bertrand Houette: Few historical characters have died in their sleep!

What is this book at the end of the day ? An adventure book, a love story, a historical novel, a spiritual quest?

Jean-Daniel Baltassat: If we have achieved our aim, it has something of all of these elements. In any event, it incorporates all the sensations we experienced.

Antoine Audouard: an initiation novel… in the style of a serialised feature story. A Roundtable which has mysteriously become Andean/gained an Andean setting…

Bertrand Houette: And there is the mythical dimension as well, this dream which has taken the name Eldorado… There still exist today legends about an Eldorado hidden in the forest!

Antoine Audouard: It’s also true to say that gold is one of the protagonists, in the shape of a statue made of solid gold! We call it the Twin Brother, as it is a replica of the mummy of the King. And this statue is searched for high and low throughout the book, and it thus symbolises the complexity of the motivations fuelling each and every character in the saga… For the Incas, it is the symbol of their history, of their links with the sacred. For the Spaniards, it is made of gold and therefore suitable for being melted down… But with the passing of time, and the fact that the statue continually escapes capture, it becomes a myth for everyone …

And does the statue exist for you?

Bertrand Houette: We no longer know whether or not it exists: we still search for it and no doubt will continue do so for many years to come, because we live within our dream.